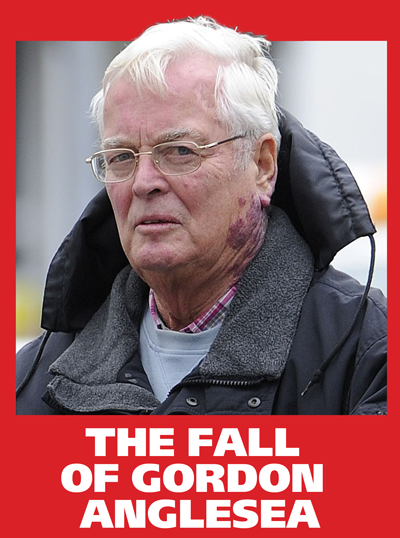

The Death Of Gordon Anglesea

CONVICTED PAEDOPHILE Gordon Anglesea died yesterday morning of natural causes.

He would have been 80 in four months.

A spokesman for the Ministry of Justice, which administers the Prison Service, this afternoon scotched rumours the retired police superintendent may have tried to take his own life.

He was taken ill a few days ago.

He had served just 42 days of a 12 year sentence for abusing two boys in the 1980s.

He was incarcerated at Rye Hill prison, a Category B training establishment, in the Warwickshire village of Willoughby.

It has a capacity of 664 inmates.

A spokeswoman at Rugby’s St Cross Hospital would not confirm that he was a patient there.

In November Anglesea was sentenced to 12 years imprisonment on four counts of indecent assault on two boys.

The first victim was abused at the Wrexham Attendance Centre which Anglesea, then a police inspector, ran in the late 1970s and 1980s.

The second boy, a resident of the private Bryn Alyn care home complex run by convicted paedophile John Allen, was passed around a group of men like a “handbag”.

One of those who abused him was then uniform inspector Anglesea.

Anglesea’s conviction was a close run thing.

It’s exactly 25 years since he was first named by the Independent on Sunday.

Had he died a few months earlier his trial would never have taken place — he would have joined Jimmy Savile as a lifetime abuser who escaped justice.

Rebecca can now reveal the website is investigating three new allegations against Anglesea:

— a former resident of Bryn Alyn says Anglesea raped him in the 1970s. The victim has always refused to make a statement against the former police inspector

— in the late 1970s a woman police officer reported a serious sexual assault by Anglesea at Wrexham Police Station.

The matter was covered up: the superintendent in charge of the division, Percy Edwards, was a freemason like Anglesea.

— another police woman made a 999 call to Cheshire Police in the 1970s claiming that Anglesea had indecently assaulted her at a party.

She also declined to make a formal complaint.

Anglesea’s death means his appeal will lapse.

However, the fate of his pension remains an issue.

Police & Crime Commissioner Arfon Jones and the North Wales Police will now have to decide if his widow Sandra will benefit from Anglesea’s substantial police pension.

Normally, she would be entitled to half.

The Crown Prosecution Service has applied for a substantial contribution to the cost of the six week criminal trial.

And the National Crime Agency is investigating the possibility of bringing an action under the Proceeds of Crime Act.

In 1994 Anglesea won damages of £375,ooo — worth more than half a million pounds today — from the Observer, Private Eye, HTV (now ITV Wales) and the Independent on Sunday.

Two of our most important Rebecca articles on Anglesea follow.

The first is the only detailed account of the trial.

The shorter but comprehensive account published by Private Eye after the trial it is not available online or on UK newspaper databases.

The second piece, published in 2010, was the result of an investigation that started in 1997.

Entitled, The Trials of Gordon Anglesea it exposed the lies which helped him succeed in the 1994 libel action.

♦♦♦

TWENTY FIVE years after he was first named as a sexual predator Gordon Anglesea has been brought to book.

On Friday a jury of five women and six men branded the retired police superintendent a child abuser.

They did what North Wales Police, the judiciary — and £20 million of public money had failed to do.

They unanimously convicted him of four counts of indecent assault against two boys in the 1980s.

Anglesea is remanded on bail until November 4.

[He was later gaoled for 12 years — see Gordon Anglesea: Justice.]

Judge Geraint Walters told him “there can only be one sentence and that will be a prison sentence”.

The six-week trial was a raw, bad-tempered affair.

The jury were unhappy because they were in court for less than a third of the time.

MINUTES AFTER Friday’s verdict Rebecca revealed the existence of a new allegation against Anglesea — in 1996 he was accused of indecently assaulting a woman. Even though he lied to the police when first questioned about the incident, he was not prosecuted. Police are also investigating an alleged cover-up. One of the offences Anglesea was convicted of was first reported back in 2002 but senior officers turned a blind eye. Read more here.

The Rebecca investigation of Gordon Anglesea started 19 years ago and has cost more than £15,000 so far. The legal bill for fireproofing the resulting articles — especially The Trials Of Gordon Anglesea — came to £6,000.

The next major piece — A Force For Evil — reveals how Anglesea was protected by the North Wales Police and escaped censure in both the 1996-1997 North Wales Child Abuse Tribunal and the more recent Macur Review.

Rebecca is independent, takes no advertising, allows no sponsorship. She relies on readers who support fearless investigative journalism …

The Rebecca investigation of Gordon Anglesea started 19 years ago and has cost more than £15,000 so far. The legal bill for fireproofing the resulting articles — especially The Trials Of Gordon Anglesea — came to £6,000.

The next major piece — A Force For Evil — reveals how Anglesea was protected by the North Wales Police and escaped censure in both the 1996-1997 North Wales Child Abuse Tribunal and the more recent Macur Review.

Rebecca is independent, takes no advertising, allows no sponsorship. She relies on readers who support fearless investigative journalism …

At one point the judge warned the trial was in danger of becoming a “pantomime”.

What follows is a long, detailed account of one of the most important court cases in recent Welsh criminal history.

It is unsparing and some readers may find it harrowing …

♦♦♦

WHEN 79-year old Gordon Anglesea walked into Court No 1 at the Law Centre in Mold on September 5, the press benches were packed.

Reporters from Channel 4, ITV and BBC watched as the retired policeman was searched by a security guard and took his seat in the dock.

The dock is surrounded by thick plate-glass.

Also present were journalists from the Press Association, representing the national press, Private Eye, the local Daily Post — and Rebecca.

The trial emerged out of the new investigation into historic child abuse in North Wales ordered by David Cameron in 2012.

The Prime Minister’s decision followed the claim by former care home resident Stephen Messham that he’d been abused by the senior Tory politician Lord McAlpine.

The allegation was made on the BBC Newsnight programme but later shown to be based on mistaken identity.

By then the new police investigation — Operation Pallial — was already underway.

Stephen Messham was one of three men who accused Gordon Anglesea of abusing them as children.

THERESA MAY

THE PRIME MINISTER was Home Secretary when she announced a police inquiry into historic child abuse in North Wales in November 2012. When Labour MP Paul Flynn asked her to examine material from Rebecca, she told him police “will, indeed, be looking at that historical evidence. That is part of the job they will be doing.”

Photo: PA

THE PRIME MINISTER was Home Secretary when she announced a police inquiry into historic child abuse in North Wales in November 2012. When Labour MP Paul Flynn asked her to examine material from Rebecca, she told him police “will, indeed, be looking at that historical evidence. That is part of the job they will be doing.”

Photo: PA

The trial in 1994 is one of the most celebrated cases in British libel history.

The jury found for Anglesea by 10-2.

In the settlement that followed, he received £375,000 in damages.

Now — 22 years later — Gordon Anglesea was back in court.

This time not as a plaintiff in a civil case but in the criminal dock as the defendant.

The original indictment accused the retired superintendent of 10 counts of abusing four boys.

The prosecution decided not to proceed with six incidents involving two alleged victims.

This meant Anglesea faced four charges.

He was accused of two counts of indecent assault and one of buggery against a boy of 14 between September 1981 and September 1982.

He also faced a single charge of indecent assault against a second boy of 14 or 15 in 1986 or 1987.

Several days of legal argument and a short adjournment meant that Eleanor Laws, QC did not start to present the prosecution case against Anglesea until Wednesday, September 14.

She told the jury she would present the evidence of the two complainants.

In addition, she would call a series of witnesses who would give evidence in support of their testimony.

♦♦♦

Complainant One is a troubled man of 48.He cannot be named for legal reasons.

The jury watched him give his evidence in chief in a series of recorded DVDs.

He then took the stand, waiving his right to do so behind screens.

He told the court he was an alcoholic who also took drugs and had a history of serious mental illness.

He had a long criminal record — mainly burglaries — but told the court he’d not been in trouble for many years.

He did not come forward until he told a counsellor about the abuse in 2015.

The jury heard that in 1982 he was ordered to spend 18 hours at the Wrexham Attendance Centre .

He was 14 at the time

The centre was part of a nationwide Home Office initiative in the late 1970s, designed as an alternative to youth custody.

The boys’ detention took place on alternate Saturday afternoons at St Joseph’s School in Wrexham.

WREXHAM ATTENDANCE CENTRE

FOR NEARLY eight years the centre was based at St Joseph’s School in Wrexham. Magistrates ordered boys to spent several hours detention every other Saturday in a military-style setting.

FOR NEARLY eight years the centre was based at St Joseph’s School in Wrexham. Magistrates ordered boys to spent several hours detention every other Saturday in a military-style setting.

The centre ran from 1978 to 1986.

For most of that time it was run by Gordon Anglesea, then a North Wales Police inspector, assisted by several other police officers.

Complainant One said the routine was gym and a race in a field followed by showers and a woodwork lesson.

He was a good runner and easily won the races in the initial series of sessions.

He said Anglesea then ordered him to start later to give the other boys a chance.

As a result he came last and showered alone.

On three of these occasions Anglesea sexually abused him.

The first time he was naked after his shower when Anglesea brushed his arm against his genitals.

Anglesea was “saying some nice things”.

Looking back, he believes the police inspector was testing him to see if he would protest.

He didn’t.

The second time, Anglesea told him to kneel over a bench while still naked — and then penetrated his anus with his finger.

Anglesea was charged with indecent assault for these two alleged offences.

On the third occasion the complainant said he was forced over the bench again — and Anglesea penetrated him either with his finger or his penis

Anglesea was charged with buggery or the alternate count of indecent assault.

The complainant blamed the abuse by Gordon Anglesea for most of his problems:

“He’s wrecked my life. He has, he’s wrecked my life. I’m an … alcoholic.”

“I’ve been in prison all me life and everything just because I hate police and everybody because of him.”

Several times he dramatically pointed to Gordon Anglesea — and insisted he was the man who abused him.

Tania Griffiths QC, defending Anglesea, put it to him he’d made a mistake about Anglesea’s distinctive strawberry birthmark.

He’d described it as being on the wrong side of his face.

The complainant replied that it was a long time ago but he was certain Anglesea abused him.

Griffiths also put it to him that the benches in the changing room were too small for him to be abused on one.

He said that’s where the abuse took place.

Griffiths also put it to him that he’d heard about Anglesea from other people and on social media.

He denied it.

She asked:

“You’re a liar, aren’t you?”

He replied:

“Believe what you want to believe.”

Complainant One said he wanted Anglesea to get his “upandcommance.”

“He’s wrecked people’s lives and he needs to pay for it”.

♦♦♦

THE PROSECUTION called several witnesses in support of Complainant One’s story.Paul Godfrey was one of the most important.

Not only did he give evidence about the attendance centre, he would also claim to have seen Anglesea in a hotel room with a homosexual market trader and an underage boy.

Godfrey was 15 when he was ordered to spend 24 hours at the attendance centre in 1980.

He’d been convicted of burglary and theft.

He said that when the boys were showering after gym Anglesea would stand at the entrance “ogling” them.

Godfrey said Anglesea did not touch him.

“UPANDCOMMANCE”

ONE OF the complainants against Gordon Anglesea said his life has been ruined by the abuse — he wanted the man who assaulted him to get his “upandcommance”.

Photo: Trinity Mirror

ONE OF the complainants against Gordon Anglesea said his life has been ruined by the abuse — he wanted the man who assaulted him to get his “upandcommance”.

Photo: Trinity Mirror

Godfrey was emphatic: he’d seen Anglesea watching the boys showering.

Two other witnesses can’t be named for legal reasons.

Witness “Alpha” gave his evidence behind screens.

He spent 24 hours at the attendance centre in 1986 when he was 16.

He’d been convicted of theft and assault.

He said Anglesea was always present when the boys were showering — looking at their bodies.

Defence QC Tania Griifiths said he’d made this up:

“It’s absolute nonsense, isn’t it?”

“Alpha” said it was the truth.

Griffiths put it to him he wanted revenge on the former policeman for family reasons.

He denied this.

Another man — who also can’t be named for legal reasons — gave evidence.

Witness “Bravo” spent 18 hours at the attendance centre in 1983 after a conviction for assault.

He said Anglesea was always present in the showers.

But he went further.

He said that on one occasion Anglesea ordered some boys to do sit-ups and squat thrusts while naked after the showers.

“Bravo” said on one of these occasions he was ordered to lie on his back and open and close his legs while Anglesea watched.

“Bravo” was asked:

“Have you come to court to tell lies?”

“No,” he replied.

The next witness to give evidence came forward during the trial.

Jason Ellis had seen reports about the attendance centre in the local paper, the Wrexham Leader.

He told the court he served 24 hours at the attendance centre in 1982 for offences including burglary.

He said he remembered reading reports of the libel action in 1994 of allegations that Anglesea watched boys in the showers.

At the time Ellis told his wife:

“that’s exactly what happened when I was there.”

Tania Griffiths suggested Jason Ellis was simply repeating allegations which had been made on the internet.

He said he remembered only what he’d seen.

Christina Ellis gave evidence confirming her husband’s testimony — it stuck in her memory because it was the first time he’d ever mentioned the attendance centre.

One of the police officers who assisted Anglesea in running the attendance centre was Graham Butlin.

Butlin was too ill to give evidence but his son Michael, a serving North Wales Police officer, made a statement.

Michael Butlin said he’d been to the centre with his father.

The prosecution called him to give evidence about this.

When he arrived at court, however, PC Butlin said he wanted to change his statement — and removed the section which supported the prosecution.

He was not called.

The jury never heard what he had to say about the centre …

♦♦♦

THE ALLEGATION of sexual abuse made by the second complainant was different to those made by Complainant One.Complainant One said his abuse took place when he was alone with Anglesea.

Complainant Two claimed Anglesea abused him when others were present.

He said he became the plaything of a paedophile ring and was handed around like “a handbag”.

Aged 44, he’s currently serving a four-year sentence and was brought to court from gaol.

He gave his evidence behind screens — only the judge, jury and the barristers could see him.

He was often volatile and at one point said he wanted to stop giving evidence:

“I feel I’m going to explode”.

The judge persuaded him to carry on.

Many of his problems, he believed, came from the abuse he’d suffered.

It was only through counselling that he had begun to understand the significance of what had happened to him.

In 1986 he was sent to the private Bryn Alyn children’s home where he was indecently assaulted by the owner, John Allen.

In 1994 Allen was sentenced to six years for abusing six boys in his care.

The complainant was not one of them — and he did not report his alleged abuse to the police who were investigating Allen.

He told the court he was bullied by the other boys.

When he went to John Allen to ask him to stop it, Allen abused him:

“ … he was saying I’m a special person … they have, special people have relationships, men and boys, and they keep it a secret.”

PIED PIPER

JOHN ALLEN was paid £30 million by local authorities to look after problem children between 1974 and 1991. He built an empire of private children’s homes in North Wales but was selecting vulnerable boys for abuse. He’s currently serving a life sentence — in all he was convicted of abusing 25 children in his care.

JOHN ALLEN was paid £30 million by local authorities to look after problem children between 1974 and 1991. He built an empire of private children’s homes in North Wales but was selecting vulnerable boys for abuse. He’s currently serving a life sentence — in all he was convicted of abusing 25 children in his care.

It wasn’t until 2001 that North Wales Police came to see him as part of a second investigation into John Allen.

Detectives told him another former resident claimed the complainant had seen John Allen abusing him.

Complainant Two said this wasn’t true.

But he told detectives Allen had indecently assaulted him.

He also said that Allen allowed other men to sexually abuse him — but did not identify them.

In 2002 officers from North Wales Police interviewed him again.

This time he handed them a piece of paper with details of three of his alleged abusers.

The jury were shown a copy of this document.

There were three names on it: “Peter”, “Norris” and “Gordon”.

“Peter” is Peter Howarth, the former deputy head of the local authority-run Bryn Estyn home.

He died of a heart attack in 1997 while serving a ten year sentence for the sexual abuse of boys at Bryn Estyn.

“Norris” is Stephen Norris, a former housemaster at Bryn Estyn.

He served two prison sentences after admitting abusing boys in his care.

In 1990 he was given three and a half years, in 1993 it was seven.

“Gordon”, according to a note on the piece of paper the complainant handed to police, is described as:

“5’9”, mid build, mousey brown well kept, prim and proper dressed, birthmark on face, had blue a piercing stare, said I was dirty and he could have me in jail if I told lies, big glasses.”

Complainant Two said he hoped detectives would “latch on” to the significance of his description and “put two and two together”.

He said they didn’t.

“GORDON”

NORTH WALES POLICE are investigating the 2002 failure to follow up the allegation that Gordon Anglesea was an abuser. A spokeswoman said: “we can confirm that … Professional Standards Department have received a complaint as a result of Operation Pallial that is being investigated.”

NORTH WALES POLICE are investigating the 2002 failure to follow up the allegation that Gordon Anglesea was an abuser. A spokeswoman said: “we can confirm that … Professional Standards Department have received a complaint as a result of Operation Pallial that is being investigated.”

He said John Allen used to take him to various houses where he would be expected to carry out cleaning duties.

Often there would be other men there who, after he’d finished his tasks, would abuse him.

He said that on one occasion he was taken to what he described as a “sandstone house” in Mold — with a long driveway and no gate.

“One fella there, I can’t remember his name, he was a nasty horrible piece of work, he had like a birth mark on his face and he had glasses, he’s something to do with the police.”

“He grabbed me by the hair, I didn’t like him, and he wanted me to, er, perform oral sex on him and I didn’t want to. “

“And he grabbed hold of me, you know, he choked me with his penis, basically, he was really rough, it was horrible.”

“And he was threatening me, he was saying, I’d never see my parents again, he would send me away, he had the power to send me away, far, far away, and I’d never see my family again.”

He said this was the only time Anglesea abused him — on other occasions he was standing in the shadows, watching the abuse.

It wasn’t until Operation Pallial was launched that the complainant fully named Anglesea as one of his abusers.

The complainant told the court that he hadn’t named him earlier because he was afraid.

During his evidence he made a new allegation, not involving Anglesea.

This concerned a session where a dog belonging to John Allen bit his penis.

He’d been ashamed to mentioned it earlier because it concerned bestiality.

Tania Griffiths QC, for Anglesea, told the complainant:

“You’re making it all up.”

He said it was true.

He denied inventing the account of Anglesea abusing him because he was hoping it would improve his chances of parole.

She put it to him that the “sandstone house” couldn’t be found — because it didn’t exist.

It did, he said.

She also accused him of coming up with the story for compensation.

“I don’t want compensation,” he insisted, “I want justice”.

She also asked him why he hadn’t recognised Anglesea when he abused him: after all, he’d seen him a few weeks earlier at Wrexham Police Station.

The complainant said he simply didn’t realise they were the same man.

WREXHAM POLICE STATION

THROUGHOUT THE late 1970s and much of the 1980s Gordon Anglesea was based at this tower block in Wrexham, since demolished. He was a well-known policeman in the town and many boys knew him from the Wrexham Attendance Centre. His nickname was “Wacman”.

THROUGHOUT THE late 1970s and much of the 1980s Gordon Anglesea was based at this tower block in Wrexham, since demolished. He was a well-known policeman in the town and many boys knew him from the Wrexham Attendance Centre. His nickname was “Wacman”.

He insisted it was true — and would allow a doctor to medically examine him.

(Later in the trial, this examination took place.

A doctor told the court that the scarring referred to was, in fact, a natural feature of the underside of his penis.

He agreed that any injury could have healed without leaving any permanent scar)

The complainant admitted to a long criminal record.

“I’m a bad man,” he said.

He became a burglar to make money.

“But before that, you know, in my early years I used to go and burgle houses, not take nothing, just smash the houses up, just so that person could hate me as much as I hated myself.”

♦♦♦

THE PROSECUTION were painting a picture of Gordon Anglesea as a police officer who took a close interest in young boys.He ran the attendance centre for many years and his patch included the Bryn Estyn and Bryn Alyn children’s homes.

He began the unusual practice of cautioning boys at both homes when it was normally done at the police station.

There was also evidence that he knew homosexuals and known or suspected paedophiles.

One of these was a market trader called Arthur who often rented a room at the Crest Hotel — now the Wynnstay Arms.

Arthur’s full name was not given in the trial.

From other sources, Rebecca has identified him as Arthur Connell.

A known homosexual, he has a conviction for indecency.

Paul Godfrey — who had given evidence about the Wrexham Attendance Centre — said he was a regular visitor to Connell’s room at the Crest Hotel in the late 1970s.

In his early teens he skived off school to work on Connell’s stall at Wrexham’s Monday market.

Another boy who helped was Mark Humphreys, known as Sammy.

Sammy was also a frequent visitor to the hotel room.

(The jury were not told that Mark Humphreys was one of the first to allege abuse at the hands of Gordon Anglesea.

He gave evidence at the libel trial in 1994 but the jury didn’t believe him.

He was found dead in his Wrexham bedsit in 1995.)

Paul Godfrey said that while they were in the hotel room, Connell would take a shower and parade around naked before getting into bed.

He would invite the boys to have showers as well — and then give them money to have their photos taken.

Godfrey was suspicious of him.

He wanted the money but would only be photographed covered by a towel.

But Sammy, he told the court, would often get into bed with Arthur.

He said there was talk — “rife, really rife” — that Sammy was involved sexually with Arthur.

One day there was a knock on the door.

It was Gordon Anglesea.

Godfrey said Anglesea wasn’t happy he was there — he told Connell to get rid of him.

Godfrey later reported the incident to a detective called Gwyn Harris.

He says Harris — now dead — didn’t believe him.

♦♦♦

THE EVENTS of 1982 became one of the key battlegrounds of the trial.The prosecution case was that Gordon Anglesea got to hear of Godfrey’s talk with Gwyn Harris — and tried to coerce him into silence.

The defence argued there was no evidence to back this up.

Godfrey told the court that his relations with the police were troubled even before the incident at the Crest Hotel.

He said that on one occasion he was beaten up by a police officer called Paul Glantz.

Godfrey was then charged with being drunk and disorderly.

CLIMATE CHANGE

THE SHADOW of Jimmy Savile — who used celebrity to mask widespread abuse of children — hung over the Anglesea trial. Anglesea’s barrister warned the jury not to be swayed by emotion …

Photo: PA

THE SHADOW of Jimmy Savile — who used celebrity to mask widespread abuse of children — hung over the Anglesea trial. Anglesea’s barrister warned the jury not to be swayed by emotion …

Photo: PA

The case was dismissed — and the police officer charged with false imprisonment.

Glantz was tried at Chester Crown Court but acquitted.

Godfrey said that things got worse when he told Gwyn Harris about Anglesea’s visit to Arthur Connell’s hotel room.

He was in the Crest sometime later when, out of the blue, Gordon Anglesea suddenly appeared.

Anglesea said:

“You’ve been to the police station, you’ve made allegations against me.”

Anglesea warned him he was asking for a “hard time”.

In November 1982 Godfrey was accused of stealing Wrigleys chewing gum from a newsagents in Wrexham.

He was kept in the cells overnight.

He was angry that he was held for the alleged theft of what he said was just £2.90 worth of gum — and believed Anglesea was behind the decision.

He claimed Anglesea came to his cell and said:

“I told you. You better keep your mouth shut about what’s going on.”

The prosecution drew attention to an entry in Anglesea’s 1982 pocketbook which made it clear he knew Paul Godfrey.

This entry — made the month before the incident with the chewing gum — concerned a file on Paul Godfrey which had gone missing.

Anglesea wrote in his pocketbook that he spoke to Paul Glantz about this and “told him I was looking for the file”.

He added that the file was wanted “urgently” because there was a “complaint against police.”

The prosecution did not say it, but the implication was that there might have been a record in the file about Godfrey reporting Anglesea’s alleged visit to the Crest Hotel.

The defence said there was a perfectly innocent explanation for Anglesea wanting the file — Godfrey had made a complaint against Paul Glantz.

Tania Griffiths, defending Gordon Anglesea, added that the file had apparently turned up a few days later.

Griffiths put it to Godfrey there was a perfectly good reason to remand him over the chewing gum incident — there were other outstanding offences.

Godfrey was adamant he’d been victimised.

Griffiths also took him to the statement he’d made to police investigating child abuse in the 1990s.

She said he’d stated:

“I’ve no complaints to make about this period of my life.”

Godfrey said he didn’t trust the North Wales Police.

The prosecution also introduced a statement taken from the deputy manager of the Crest Hotel in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Christopher Appleton said young boys between the ages of 10 and 16 would go up to Arthur’s room.

He assumed they were helping on the market stall.

One of these, a boy of 12 or 13, became a “bit of a pest” by turning up on Sundays asking for Arthur.

It was implied — but not stated — that this was Mark “Sammy” Humphreys …

♦♦♦

THE PROSECUTION also brought evidence alleging Gordon Anglesea had links with the ringleader of a paedophile ring in Wrexham.This was Gary Cooke, a man who used aliases to conceal the fact he had a long string of child abuse convictions.

In 1979 police discovered photographs hidden in a hollowed out book at his home.

One of these was an indecent photo of Mark Humphreys.

In 1980 Cooke was gaoled for five years for a series of offences, one of which related to this photograph.

RINGLEADER

GARY COOKE is one of the most active child abusers in North Wales. He was the organiser of a paedophile ring which systemically abused boys at his home. In October 2015 Cooke and four associates — including former Metropolitan Police officer Edward Huxley and BBC radio presenter Roy Norry — were gaoled for a total of 43 years on 32 counts of sexual abuse.

Photo: Trinity Mirror

GARY COOKE is one of the most active child abusers in North Wales. He was the organiser of a paedophile ring which systemically abused boys at his home. In October 2015 Cooke and four associates — including former Metropolitan Police officer Edward Huxley and BBC radio presenter Roy Norry — were gaoled for a total of 43 years on 32 counts of sexual abuse.

Photo: Trinity Mirror

“Alpha” had been sexually abused by both Cooke and John Allen, the head of Bryn Alyn.

He said he was at Gary Cooke’s home one day when Gordon Anglesea turned up:

“he knocked on the door … he [Cooke] says it’s just a friend, or whatever.”

“And I’m sat there … and, let him in … he’s just walked through, they’ve talked in the kitchen.”

“And then they’ve come through and … said their goodbyes and then he’s gone.”

The defence attacked Witness “Alpha”.

Tania Griffiths put it to him that his claim to have seen Anglesea at a house owned by Cooke was wrong.

At that time Cooke hadn’t bought it.

“Alpha” said he wasn’t lying — he’d just got the wrong address.

Tania Griffiths also homed in on an incident in which he claimed he’d been abused in the same property by a member of Cooke’s paedophile gang, the BBC radio presenter Ray Norry.

“Alpha” claimed he was being assaulted on a glass table by Norry when it broke and the BBC presenter was injured.

The defence said this incident had, indeed, happened — in March 1984 — but not at the address “Alpha” claimed.

Roy Norry received hospital treatment for a deep wound to his lower back.

The accident was witnessed by a friend.

Anglesea’s defence QC put it to “Alpha” that he couldn’t have been present.

He was lying.

“Alpha” replied that he was telling the truth.

♦♦♦

GORDON ANGLESEA, the prosecution said, also knew another convicted paedophile.This was Peter Howarth, the deputy headmaster at the local authority-run Bryn Estyn children’s home near Wrexham.

Howarth was gaoled for ten years in 1994.

A jury found him guilty of seven counts of indecent assault and one of buggery.

He died before he could complete his sentence.

Bryn Estyn was in the Bromfield section of the Wrexham police area — and Gordon Anglesea was the inspector in charge.

Anglesea said his first visit to the home did not take place until 1980 and he did not know Howarth.

The prosecution drew the jury’s attention to a letter sent by Bryn Estyn headmaster Matt Arnold to Anglesea in March 1980.

It was about Bryn Estyn boys arriving late at the attendance centre.

Arnold wrote:

“I have only just returned to work from a period of sick leave, so I’m not aware on a personal basis of all the discussions that have gone on between you and Mr Howarth.”

The prosecution also called retired police inspector Ian Kelman to give evidence.

PETER HOWARTH

THE DEPUTY HEAD of Bryn Estyn, Howarth died in prison after he was gaoled for ten years in 1994 on seven counts of indecent assault and one of buggery. Gordon Anglesea has always denied that he knew Howarth …

Photo: Press Association

THE DEPUTY HEAD of Bryn Estyn, Howarth died in prison after he was gaoled for ten years in 1994 on seven counts of indecent assault and one of buggery. Gordon Anglesea has always denied that he knew Howarth …

Photo: Press Association

On one of these occasions he saw Anglesea with Howarth.

Kelman had given a statement to this effect to the defence in the 1994 libel action but ill-health prevented him from taking the stand.

Tania Griffiths, for Anglesea, asked him if he’d given a copy of his 1994 statement to Rebecca.

“No,” he replied.

(In fact Rebecca editor Paddy French obtained a copy of the statement from the files held by HTV on the 1994 libel action when he was a current affairs producer for the company.)

The current Police and Crime Commissioner for North Wales, Arfon Jones, also gave evidence.

He’d been a police constable in the 1980s and his duties included acting as Anglesea’s driver.

“The only place I recall taking him was to Bryn Estyn children’s home.”

“If he wanted to go to Bryn Estyn he would ask me and I would take him.”

He said it probably happened half a dozen times between 1982 and 1985.

He thought Anglesea was giving cautions.

He said he dropped Anglesea off and did not come back to collect him.

JONES THE DRIVER

ARFON JONES, the Police and Crime Commissioner for North Wales, told the court he often drove Gordon Anglesea to the Bryn Estyn children’s home. He dropped him off and was never asked to go back and collect him …

Photo: Police & Crime Commissioner’s Office

ARFON JONES, the Police and Crime Commissioner for North Wales, told the court he often drove Gordon Anglesea to the Bryn Estyn children’s home. He dropped him off and was never asked to go back and collect him …

Photo: Police & Crime Commissioner’s Office

Another former policeman who gave evidence was retired police sergeant John Graham Kelly.

He worked in the Bromfield section and acted as his driver from time to time.

He was also Gordon Anglesea’s second in command at the Wrexham Attendance Centre

He was, he told the court, a friend of Gordon Anglesea’s.

He was supposed to be a prosecution witness but when he took the stand, he appeared to give evidence supporting the defence.

He told the jury Anglesea rarely gave cautions at children’s homes.

Eleanor Laws, for the prosecution, then pointed out that this comment contradicted his police statement which said:

“I’m aware that Gordon Anglesea on a very regular basis visited Bryn Estyn and Bryn Alyn and conducted cautions at their premises …”

He added it “ … almost became the norm.”

Eleanor Laws asked — which version was correct?

Kelly now accepted that his written statement was correct — not the version he’d just given in open court …

Paul Godfrey also spent time in Bryn Estyn.

He was there twice in 1981.

He said that on the second occasion he was taken to the home by Gordon Anglesea.

He said that, just inside the front door, was what he called a “holding cell”.

He says that Anglesea ordered him to strip naked while staff brought a new set of clothes for him.

Tania Griffiths, for Anglesea, asked Godfrey if he was making the whole episode up.

“The point is you’re trying to paint a bad picture here.”

Godfrey came back:

“It is a bad picture.”

♦♦♦

THE PROSECUTION also called Alan Norbury, the senior investigating officer from Operation Pallial, to give evidence.He was asked about the police interview in 2002 during which Complainant One produced the note which named a man called “Gordon” as one of his abusers.

There had been an email exchange between senior officers about this note which made it clear they believed “Gordon” was likely to be Anglesea.

Norbury was asked if these police officers should have investigated further.

Norbury replied that they should.

When Norbury was cross-examined by Tania Griffiths she asked him about the events that surrounded Gordon Anglesea’s arrest on 12 December 2013.

Anglesea was arrested and police executed a search warrant.

Ms Griffiths asked if police found anything when they searched his home.

They did not, Norbury replied.

When police seized Anglesea’s computer, the retired policeman said:

“You’ll find nothing on that.”

There was nothing incriminating on the hard drive.

When Anglesea was arrested, police did not name him.

The press release stated only that a 76-year-old male from Old Colwyn had been arrested.

Ms Griffiths then placed an article from the Daily Mirror of 22 January 2014 on the TV monitors in the courtroom.

Marked “Exclusive”, this revealed the pensioner arrested in December was Gordon Anglesea.

Ms Griffiths asked Norbury how the paper had found out.

FALSE ACCUSATION

DEFENCE BARRISTER Tania Griffiths accused the National Crime Agency [NCA] of deliberately leaking Anglesea’s name as “bait” to attract more complainants. She screened an article from the Daily Mirror as evidence of this tactic. In fact, there was no leak from the NCA — Anglesea’s name had been revealed six days earlier by Rebecca. Confirmation had come from the Rotary Club. Gordon Anglesea, who sat silent in the dock while his barrister made the allegation, knew it wasn’t true. We had warned him in a recorded delivery letter that he was going to be named. Rebecca has asked the disciplinary watchdog of the Bar Council to decide if the jury was deliberately misled on this point…

Photo: Press Association

DEFENCE BARRISTER Tania Griffiths accused the National Crime Agency [NCA] of deliberately leaking Anglesea’s name as “bait” to attract more complainants. She screened an article from the Daily Mirror as evidence of this tactic. In fact, there was no leak from the NCA — Anglesea’s name had been revealed six days earlier by Rebecca. Confirmation had come from the Rotary Club. Gordon Anglesea, who sat silent in the dock while his barrister made the allegation, knew it wasn’t true. We had warned him in a recorded delivery letter that he was going to be named. Rebecca has asked the disciplinary watchdog of the Bar Council to decide if the jury was deliberately misled on this point…

Photo: Press Association

She asked if it was someone from his team who was responsible.

He said it wasn’t.

“You were hanging him on a line,” Griffiths put it to him, as “bait” to attract other complainants.

Norbury said that wasn’t true.

Griffiths asked him if he’d carried out an inquiry to find out how the information had leaked.

He said he hadn’t.

♦♦♦

GORDON ANGLESEA took the stand at 2.45 on Thursday afternoon, 6 October 2016.He was dressed in a dark blue wide pin-striped suit with a tie.

He took the oath in a loud, confident voice.

He said a newspaper article in 1991 named him in such a way that it carried the “implicit suggestion” he was involved in child abuse.

Even after he won £375,000 in a high-profile libel case, he said his “nightmare” continued.

His QC Tania Griffiths asked him:

“You have heard these allegations made against you — have you ever behaved inappropriately to any boys?”

Anglesea replied:

“None whatsoever, to any child.”

He said the Wrexham Attendance Centre was run on military lines and that boys were not allowed to talk throughout the sessions.

The court did not sit the following day which meant that the prosecution could not cross-examine until Monday, October 10.

♦♦♦

IT WAS TO be one of the most dramatic days of the entire trial.Prosecutor Eleanor Laws QC asked Anglesea about the witnesses who said they’d seen him watching boys in the showers at the attendance centre.

“You’re the victim of malicious lies?”

“That is correct,” said Anglesea.

Laws pointed out that when he gave evidence on oath the previous Thursday he’d told the jury he visited the shower area at the attendance centre “once or twice”.

But when he gave evidence to the 1994 libel trial his evidence was different.

She read from the transcript

Anglesea was asked:

“Did you stand in the showers watching the boys regularly, Mr Anglesea?”

He replied:

“I went to the showers on every occasion the attendance centre was open.”

He was asked:

“… it was not because, in fact, Mr Anglesea, you liked looking at young boys in the nude?

He replied.

“Absolutely totally untrue.”

Between 1978 and 1986 there had been something like 150-160 sessions of the attendance centre.

Anglesea had been given the transcript of the libel action to read over the weekend.

He now told the court:

“I read it and I realised there was an interpretation on there which to me was incorrect.”

Eleanor Laws said he was trying to “wriggle out of the fact you said two vastly different things.”

She accused him of lying under oath, either during the libel action or to the present jury.

Anglesea replied:

“I have made nothing up at all.”

He was also asked why he started giving cautions at the privately owned Bryn Alyn homes as well as at Bryn Estyn.

At Bryn Estyn he started because the principal was short-staffed.

But at Bryn Alyn he did it because it was “more convenient for the police”.

So who did he arrange these cautions with?

“Somebody,” answered Anglesea, “a member of staff.”

Anglesea was questioned again by Tania Griffiths.

He claimed all the allegations against him were “in my belief … part of a conspiracy.”

That conspiracy emerged in the wake of the Savile scandal “purely to obtain compensation”.

It was, he said, “abhorrent”.

♦♦♦

THE DEFENCE called several witnesses in support of Anglesea.Retired teacher George Sumner had been a woodwork instructor at the Wrexham Attendance Centre.

Tania Griffiths asked him if he’d ever seen anything that made him uncomfortable.

“Nothing whatsover.”

Former Bryn Alyn resident Mark Taylor told the court he attended the centre in 1984 and again in 1986.

He was impressed by Gordon Anglesea: he and the rest of the staff were “fantastic people”.

He enjoyed the attendance centre so much that he continued going after his sentence was complete.

He kept in touch with Anglesea afterwards.

Retired traffic sergeant David Edwards told the court he first met Gordon Anglesea in 1966.

Anglesea was in Flintshire CID at the time.

Edwards said:

“He was one the best detective constables I ever knew.”

“I admired him.”

He was cross-examined by Eleanor Laws about statements he made about Gordon Anglesea’s visits to Bryn Estyn.

Edwards had said:

“I would like to add that Gordon would regularly attend Bryn Estyn for meetings on boys’ progress.”

He also told the court there was one occasion when Anglesea asked him to take the session because he had a masonic function to attend.

Anglesea turned up later in what Edwards described as “masonic gear”.

Edwards said there was a rule that they didn’t wear uniforms at the centre.

JUDGE GERAINT WALTERS

Rebecca wrote to the judge before the trial asking him to make a statement about freemasonry. Our letter pointed out that Anglesea is a former mason and that the judge in the 1994 libel action, Maurice Drake, made it clear he was a member of the same organisation. Judge Walters did not reply to the letter — and did not make any comment about freemasonry. We do not know if he is, or ever has been, a mason. The United Grand Lodge in London— the governing body of freemasonry — told us Gordon Anglesea resigned his membership in 2007.

Rebecca wrote to the judge before the trial asking him to make a statement about freemasonry. Our letter pointed out that Anglesea is a former mason and that the judge in the 1994 libel action, Maurice Drake, made it clear he was a member of the same organisation. Judge Walters did not reply to the letter — and did not make any comment about freemasonry. We do not know if he is, or ever has been, a mason. The United Grand Lodge in London— the governing body of freemasonry — told us Gordon Anglesea resigned his membership in 2007.

Another retired police officer, Thomas Harrison, also gave evidence.

His job was to take PE and he said there were always two members of staff on duty.

He confirmed that there were races in the field outside.

Tania Griffiths asked him:

“Was any boy ever held back?”

“No,” said Harrison.

“Was Gordon Anglesea ever there?”

“No.”

Asked about the boys taking showers, he said something extraordinary:

“I can’t remember anybody having showers”.

No other witness had made this claim — not even Gordon Anglesea.

Cross-examined by Eleanor Laws, he was asked how he could possibly forget about the showers.

He said he just couldn’t remember them.

She pointed out that the boys had to change for PE — and that the showers were part of the changing rooms.

Harrison said he thought the boys changed in the gym …

♦♦♦

IN HER closing speech, Eleanor Laws told the jury that the complainants had been “raw, credible and real”.She said that if they were lying then they had given “Oscar-winning performances.”

She urged the jury not to “leave your common sense at the door of the jury room.”

Defence barrister Tania Griffiths said the complainants “told whopping great lies.”

It was a “conspiracy” and done with “concerted and malicious intent”.

She said the prosecution had homed in on “the one mistake” — the discrepancy between Anglesea’s evidence about how often he was in the changing rooms at the attendance centre.

This was a mistake, she said — he didn’t go to the showers area every time.

Tania Griffiths warned the jury against making a decision on the basis of “no smoke without fire”.

She was obviously concerned that the post-Savile climate might influence the jury.

She said that no-one in the country would now say Savile was innocent.

But the jury should judge Anglesea not on the basis of emotion but on the evidence.

She told them about the Cliff Richard case where the singer claimed he was wrongly accused.

She also raised the television drama National Treasure where the character played by Robbie Coltrane was acquitted only for the viewer to see him actually raping his victim.

♦♦♦

THE jury started their deliberations at 9.55 on Thursday morning.They had actually been in court for less than a third of the six week trial.

Many days were spent by the barristers arguing points of law.

The atmosphere in the court often became heated during these exchanges.

On one occasion prosecution QC Eleanor Laws accused Tania Griffiths, for Anglesea, of being “overdramatic” — branding her style “unattractive” and “offensive”.

Griffiths attacked Laws for trying to control her.

When Laws said she was trying to get “robust management of the case,” Griffiths snapped back:

“What she’s doing is robust management of me.”

On another occasion Griffiths complained Laws was constantly bringing up her greater experience in criminal law.

“It’s very wearing,” said Griffiths, “It’s very rude indeed.”

Again and again she complained the prosecution had disclosed material late.

Dogged and relentless, she tried repeatedly to widen the scope of the trial to include the events of the early 1990s.

She said Gordon Anglesea was a man who was falsely targeted by journalists and that witnesses had to be persuaded to make allegations against him.

The judge insisted the present trial could only deal with the evidence relating to the actual allegations on the indictment.

At one point he lost patience.

He said Tania Griffiths’ style was all wrong and he was “finding it tiresome in the extreme”.

“This is not a stage show”.

♦♦♦

THE JURY returned at 1.40 on Friday afternoon.The atmosphere in Court No 1 was electric.

A court official asked Gordon Anglesea to stand.

She then asked the forewoman of the jury if their verdicts were unanimous.

She said they were.

The official then read out the first count on the indictment.

This was the indecent assault on Complainant One in the showers at the attendance centre.

She asked the forewoman to answer guilty or not guilty.

In a clear, emphatic voice she said:

“Guilty”.

Within seconds Rebecca tweeted the verdict.

There was a similar verdict on the second count, the indecent assault in the showers.

On the third count, the alleged buggery, the result was “not guilty”.

But the jury found Anglesea guilty of the alternate charge of indecent assault.

On the final count, the indecent assault on Complainant Two, the jury delivered another guilty verdict.

Anglesea was remanded on bail until November 4.

Judge Geraint Walters told the now disgraced former policeman:

“You know yourself already that there can only be one sentence and that will be a prison sentence.”

Anglesea had planned to make a statement outside the court if he’d been cleared.

Now the court and the police agreed to sneak him out of the back door of the Mold court complex.

The media were not impressed …

♦♦♦

AN EXTRAORDINARY case was over.No-one can know what went on in the jury room but one clue emerged.

Soon after they started discussing the case, the jury sent the judge a note.

NEMESIS

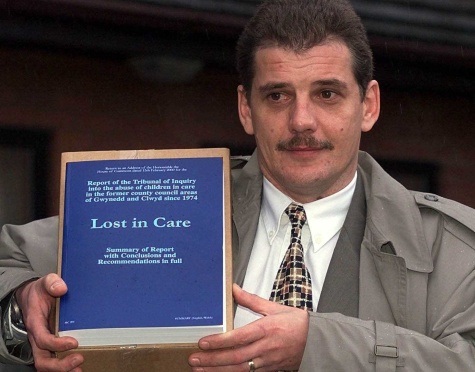

STEPHEN MESSHAM, seen here at the launch of the Waterhouse Tribunal report in 2000, is one of the key figures in the North Wales child abuse saga. He was also the trigger for the police investigation that led to the fall of Gordon Anglesea. In 2012 on the BBC Newsnight programme he named Lord McAlpine as one of his abusers. By the time he’d realised it was a case of mistaken identity, Operation Pallial was already under way …

Photo: PA

STEPHEN MESSHAM, seen here at the launch of the Waterhouse Tribunal report in 2000, is one of the key figures in the North Wales child abuse saga. He was also the trigger for the police investigation that led to the fall of Gordon Anglesea. In 2012 on the BBC Newsnight programme he named Lord McAlpine as one of his abusers. By the time he’d realised it was a case of mistaken identity, Operation Pallial was already under way …

Photo: PA

Arnold said he was not “aware on a personal basis of all the discussions that have gone on between you and Mr Howarth.”

Howarth was the deputy head, later to be convicted of abusing boys at Bryn Estyn.

Anglesea claimed he didn’t know him.

Asking for the letter to be read out again suggests one of the jury’s key considerations was Anglesea’s credibility as a witness.

For a quarter of a century he’d tried to avoid being tarred with Howarth’s paedophile brush.

Anglesea also resisted attempts to place him in the changing rooms at the attendance centre.

But he was badly damaged by the fact that he gave two different versions — one at the libel trial and a completely different one at Mold Crown Court.

Even some of the police officers the prosecution called gave questionable testimony.

The evidence of Thomas Harrison, the PE teacher who couldn’t remember boys taking showers, was plainly hard to believe.

The jury may have wondered if he remembered perfectly well — but that he might have seen something he didn’t want to reveal.

Retired sergeant Graham Kelly made a statement saying Anglesea cautioned often at both Bryn Estyn and Bryn Alyn.

But when he was in the witness-box, he tried to say the opposite — only to be forced by prosecution barrister Eleanor Laws to admit his statement was correct.

Kelly — a man who enjoys a reputation as a decent, honest officer — cut a sorry figure in the dock.

He was uncomfortable and gave the impression he knew a great deal more about Anglesea than he was prepared to say.

And what of serving officer Michael Butlin?

He accompanied his father when he was employed to help Anglesea run the attendance centre.

He gave a statement to Operation Pallial but amended it on the day he was due to give evidence.

The change meant his testimony was worthless to the prosecution.

♦♦♦

IN THE END, the verdict probably comes down to the changed climate in which historic child abuse cases take place.In the old days, people who complained of child abuse were damaged souls who had to battle against the poor impression they inevitably presented in the witness-box.

Their alleged abusers normally held positions of power and authority and invariably made a good impression on juries.

This was doubly so in the case of police officers.

Today everything is different.

Juries understand allowances have to be made for the effects of the damage suffered by claimants.

And they subject suspected abusers to greater scrutiny.

In Gordon Anglesea’s case they decided his evidence did not stand up to serious scrutiny.

His fatal weakness was a simple one — he never behaved like an innocent man …

♦♦♦

Published: 23 October 2016© Rebecca

♦♦♦

THE TRIALS OF GORDON ANGLESEA

GORDON ANGLESEA, the former North Wales Police superintendent, is an enigma.

On the one hand he won a famous libel action which saw some of the country’s biggest media companies pay£375,000 in damages for falsely accusing him of sexually abusing young boys.

On the other, he was an important character in the events which led up to the decision to set up the north Wales Child Abuse Tribunal in 1996.

He was a senior police officer and a freemason in a situation where critics were alleging that the police were covering up child abuse, some of which was laid at the door of freemasons.

The Tribunal could find no evidence that would have persuaded the libel trial jury to change its mind.

But its three members expressed “considerable disquiet” about some of the evidence Anglesea gave when he appeared before them.

And now a Rebecca investigation reveals that the judge in his libel action also shares that “considerable disquiet”.

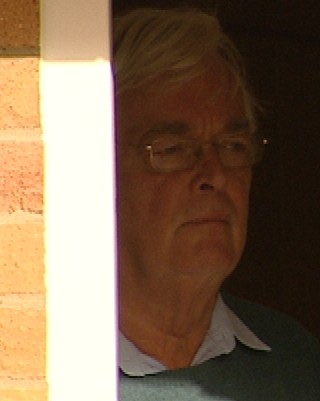

GORDON ANGLESEA

The North Wales Police superintendent won a major libel case against journalists who accused him of abusing young boys at the Bryn Estyn children’s home outside Wrexham.

Photo: Rebecca

The North Wales Police superintendent won a major libel case against journalists who accused him of abusing young boys at the Bryn Estyn children’s home outside Wrexham.

Photo: Rebecca

This is the cockpit where some of the country’s most celebrated libel trials have been played out.

They include the Jonathan Aitken and Jeffrey Archer cases.

The 57-year-old Anglesea was in Court 13 because he had sued two national newspapers, The Observer and the Independent on Sunday, the magazine Private Eye and HTV, the holder of the ITV franchise in Wales.

His legal costs were underwritten by the Police Federation.

Anglesea claimed the four defendants had accused him of being a child abuser during visits he made to the Bryn Estyn children’s home just outside Wrexham.

The judge, Sir Maurice Drake, was a veteran of many libel actions.

Like Gordon Anglesea, he was a freemason, but he declared that they were members of the same organisation at the start of the trial.

He retired in 1995, the year after the trial.

He told Rebecca about his memories of the case.

“For about five years as the Judge in charge of the civil jury list,” he said, “I tried a very, very large number of defamation cases. Many of them did not make any lasting impression on me; but others did and none more so than that of Supt Anglesea.”

Sir Maurice Drake, the judge in Anglesea’s dramatic libel action, unusually answered questions about the case when Rebecca wrote to him.

Photo: © Photoshop

Photo: © Photoshop

Williams was ennobled by Neil Kinnock as Lord Williams of Mostyn, and later became Attorney General.

He was to die suddenly in 2003 when he was Leader of the House of Lords.

The QC acting for Private Eye, The Observer and the Independent On Sunday was Britain’s best known libel barrister, George Carman.

He died in 2001.

It had all started three years earlier.

In December 1991 — eight months after Anglesea retired from the North Wales Police — the Independent On Sunday wrote about the police investigation into allegations of child abuse at the Bryn Estyn children’s home in North Wales.

The front page article stated:

“According to former residents of Bryn Estyn, Gordon Anglesea, a former senior North Wales police officer, was a regular visitor there.”

“He recently retired suddenly without explanation.”

One of the authors of the article, Dean Nelson, later claimed that this reference was not intended to imply that Anglesea was involved in child abuse.

Anglesea immediately went to his solicitor who wrote to the paper demanding an apology with damages.

The Independent On Sunday refused.

As a result of this article, the North Wales Police decided to investigate Gordon Anglesea as part of its broad-ranging inquiry into child abuse in North Wales headed by Superintendent Peter Ackerley.

The journalist Dean Nelson was sent back to North Wales to see if there were any witnesses who would testify against Anglesea.

Next into the frame was The Observer.

In September 1992 the paper stated:

“A former police chief has been named as a prime suspect in the North Wales sexual abuse scandal, police sources in the region confirmed last night…”

“The ex-police chief is due to be questioned this week as evidence emerges that staff in some children’s homes ‘lent’ children to convicted paedophiles for week-ends.”

When the North Wales child abuse inquiry investigated the latter claim, in the late 1990s, it concluded there was no evidence of children being farmed out to abusers.

The Observer did not name Anglesea but it was clear from the context that the reference could only refer to him.

The paper made similar comments in subsequent editions.

By this time Dean Nelson had found two former Bryn Estyn children who were prepared to testify they had been abused by the police officer.

BRYN ESTYN

This building just outside Wrexham used to be the Bryn Estyn children’s home where Gordon Anglesea was accused of abusing residents. Bryn Estyn closed in 1984.

Photo: Barry Davies / Rebecca

This building just outside Wrexham used to be the Bryn Estyn children’s home where Gordon Anglesea was accused of abusing residents. Bryn Estyn closed in 1984.

Photo: Barry Davies / Rebecca

The programme was watched by another former Bryn Estyn resident.

He told a BBC researcher that Anglesea had abused him and later agreed to give evidence against the former superintendent.

Finally, Private Eye entered the fray in January 1993 with an article based on research from the freelance journalist Brian Johnson-Thomas.

This article claimed Anglesea had investigated allegations against the son of the North Wales politician Lord Kenyon.

Lord Kenyon was a magistrate, a member of the North Wales Police Authority and the Grand Master of the North Wales Province of freemasonry.

Anglesea was also a freemason.

The allegations were made by one of the three men who claimed Anglesea had abused them.

The Waterhouse Tribunal also investigated this issue — and said it could find no evidence that Anglesea had ever been involved in the investigation of the allegation.

In 1993 or 1994 Superintendent Peter Ackerley, the officer heading the police investigation into child abuse at Bryn Estyn and other children’s homes across North Wales, sent a report about Anglesea to the Crown Prosecution Service.

Ackerley recommended prosecution on the grounds that there was more than one witness claiming Anglesea had abused them.

His decision was to remain secret for many years.

The CPS decided not to charge the retired superintendent.

♦♦♦

WHEN SIR Maurice Drake started proceedings in Court 13 on 14 November 1994, neither he nor the defendants were aware police had recommended that Anglesea be prosecuted.

Anglesea was the plaintiff, the defendants were the four media organisations who pleaded justification, that is that their reports were true.

Libel actions are unusual.

Normally whoever brings a case – the state in criminal prosecutions or the plaintiff in civil actions – has to prove their case.

The burden of proof does not lie with the defendants.

In libel it’s the other way round — all the plaintiff, in this case Anglesea, has to do is to prove that his reputation has suffered as a result of the coverage.

He does not have to prove his innocence.

Since the defendants pleaded justification, they had to prove that he was guilty of sexually assaulting young boys.

Gordon Anglesea gave his evidence at the start of the case.

He was easily able to demonstrate the damage that had been done to his life and reputation by the accusations of being a child abuser.

His wife Sandra also gave evidence.

She said that up to the media reports she and her husband had enjoyed a normal sex life.

At the time when the sexual assaults were alleged to have taken place their sex life was normal.

The defendants brought the three men who claimed they’d been abused by Anglesea into the witness-box.

One of them was a resident of Bryn Estyn in 1980 and 1981.

He claimed to have been indecently assaulted by Anglesea on one occasion and then buggered by him on another.

He also claimed to have been assaulted frequently by Peter Howarth who, he said, knew Anglesea well.

(Howarth had been the home’s deputy principal.

Five months before Anglesea’s libel action started, he was gaoled for ten years for abusing boys at Bryn Estyn.)

Lord Williams was able to do considerable damage to the credibility of this witness by pointing out inconsistencies between several of his statements and variations in his accounts of the assaults.

Another witness was a resident of Bryn Estyn in the late 1970s.

He said he had anal and oral sex with Anglesea on several occasions.

He also claimed to have been buggered by Howarth between a dozen and two dozen times.

He too insisted that Anglesea and Howarth knew one another.

This witness was allowed to take tranquillisers while he was giving evidence and the jury were informed.

However, he collapsed in the dock and proceedings had to be halted for him to be given medical treatment.

Lord Williams was able to undermine his testimony by highlighting inconsistencies, including an early denial in a police interview that he had been abused by Anglesea.

He also made much of the fact that he had been paid £4,500 by Private Eye in settlement of an alleged libel before he would agree to testify against Anglesea.

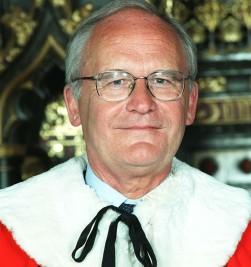

LORD WILLIAMS, QC

Lord Williams of Mostyn, Anglesea’s barrister, was able to undermine the credibility of the witnesses against his client.

Photo: © Photoshop

Lord Williams of Mostyn, Anglesea’s barrister, was able to undermine the credibility of the witnesses against his client.

Photo: © Photoshop

He claimed that he had caddied for Howarth about half a dozen times and had been introduced to Anglesea.

He alleged that Howarth and Anglesea played with his private parts while he was in Howarth’s flat at Bryn Estyn.

Lord Williams pointed out that he did not name Anglesea in his police statements.

He also made much of the fact that the witness had a serious drink and drug problem.

Lord Williams challenged all three witnesses to admit that they had fabricated their accounts.

All three insisted they were telling the truth.

The judge in the trial, Sir Maurice Drake, has told Rebecca about his memories of what happened during the fifteen days of hearings.

He started by saying “the trial took place many years ago and without refreshing my memory with the full transcript of evidence I am cautious about making comments about the case.”

But he added:

“One thing which I still have a very clear recollection of is the splendid advocacy of George Carman for the defence and Lord Williams of Mostyn for the plaintiff.”

“Although George Carman displayed all his usual skills with the jury he was, on this occasion, outshone by Gareth Williams.”

“Without Lord Williams’ advocacy I think it very possible indeed that the jury would have found for the defendants — and meeting both of them socially I told each of them that view.”

♦♦♦

ALTHOUGH LORD Williams had damaged the defendants’ witnesses this was not fatal.

Anyone who had been abused as a child and who never received a proper education was likely to be a witness with many difficulties.

Unless clear-cut forensic evidence is available, an allegation of child abuse is normally a closed issue and only the accuser and the accused can know what the truth is.

This means that other circumstantial evidence, which can be tested, becomes important.

In Anglesea’s action, there were two categories of these.

The first was the number of times he’d been to Bryn Estyn, the children’s home near Wrexham where the abuse is alleged to have taken place.

The second was whether he knew Peter Howarth, the deputy principal of Bryn Estyn, who had been convicted of child abuse at the home five months before the libel action began.

The defendants’ case was that Anglesea had been at the home on more occasions than he admitted to and that he was on friendly terms with Peter Howarth.

PETER HOWARTH

Peter Howarth, the deputy principal of Bryn Estyn, was convicted of abusing children at the home five months before the libel action began. He was given a ten-year gaol sentence for abusing seven Bryn Estyn boys over a decade. He died in prison.

Photo: Press Association

Peter Howarth, the deputy principal of Bryn Estyn, was convicted of abusing children at the home five months before the libel action began. He was given a ten-year gaol sentence for abusing seven Bryn Estyn boys over a decade. He died in prison.

Photo: Press Association

Anglesea was a uniform police inspector in Wrexham and came into contact with Bryn Estyn boys in 1979 when he was appointed to run the Wrexham Attendance Centre.

This was a Home Office initiative where magistrates could sentence boys to spend a couple of hours on a Saturday.

Then in 1980 he took over the area which included Bryn Estyn.

He was still in charge when Bryn Estyn closed in 1984.

When he was contacted by the Independent on Sunday journalist Dean Nelson, Anglesea said he had only ever been to Bryn Estyn twice for Christmas dinners.

When his solicitors wrote to the newspaper a few days later, they said that he’d been to the home on one other occasion, making three in all.

By the time he was interviewed by police in January 1992, a month after the Independent on Sunday article, the number of visits had grown to four.

As well as the two Christmas dinners and one in connection with the non-attendance at the Wrexham Attendance Centre of a boy from the home, he now remembered another.

“I can only recall visiting Bryn Estyn to caution a boy on one occasion at the request of the principal because of staffing difficulties.”

“Normally boys would attend at the police station and cautioning duties were shared with other Inspectors.”

By the time he submitted his Proof of Evidence for the libel action, in March 1994, he had been allowed to inspect his pocket books.

These dated from September 1980 — earlier ones had been destroyed in line with force policy.

He said: “I do not recall having any contact at all with Bryn Estyn before September 1980 and indeed I can think of no reason why I should have done so.”

He said his pocketbooks showed that he had given seven cautions at Bryn Estyn.

In addition, he said he had also visited the home on two other occasions on official police business.

He was always in uniform and he had never gone upstairs where Howarth’s flat was located.

With the two Christmas dinners, when he was not in uniform, that made a total of 11 visits to Bryn Estyn.

However, defence lawyers noticed that from March 1983 to February 1984 Anglesea’s notebook entries became brief with little detail beyond the times he was on duty.

Anglesea later explained this by saying it was caused by grief at the death of his four-year-old daughter in May 1983 which resulted in “a departure from my normally meticulous record-keeping.”

♦♦♦

THE SECOND area of circumstantial evidence was whether he had known Peter Howarth, the deputy principal of Bryn Estyn.

One of the men who claimed he had been abused by Anglesea, gave evidence that Howarth had introduced him to Anglesea on a golf course in Wrexham.

In July 1994, five months before the libel trial started, Howarth was sentenced to 10 years in gaol at Chester Crown Court.

He was found guilty of one count of buggery and seven offences of indecent assault on seven Bryn Estyn boys between 1974 and 1984.

One of these boys, Simon Birley, hanged himself from a tree in May the following year.

Howarth was to die in prison of a heart attack in April 1997.

In his Proof of Evidence for the libel action Anglesea was categorical about his knowledge of Howarth.

“He was not personally known to me. I have never played golf with him.”

“Indeed I last played golf in about 1968 when I disposed of my clubs.”

“I may have spoken to him on the telephone relating to the Attendance Centre.”

“If I ever met him, it has not registered, and I cannot recall him in any way.”

The defendants called two witnesses about this issue.

The first was Joyce Bailey, a part-time house-mother at Bryn Estyn between 1981 and 1984, and the wife of a police constable who had served in Wrexham.

She said Anglesea was a regular visitor to the home in an official capacity.

She remembered seeing him in casual clothes only once when he arrived in his own car.

He got out, took some golf clubs from the back of the car and gave them to Howarth.

The second was Michael Bradley, a senior probation officer, who had spent three months at Bryn Estyn in the late summer of 1980 while on a course.

He was the ex-husband of an executive at HTV who was not involved in the libel action.

He gave evidence that he was at the home one night around nine in the evening when he saw Howarth and Anglesea enter the building.

Howarth introduced him to Anglesea as a good friend of Bryn Estyn and the two men then climbed the stairs.

He said that he did not know Anglesea but recognised him when he saw pictures of him in the early 1990s.

But there is one witness who did not give evidence.

He was Ian Kelman, a retired police inspector who served in Wrexham at the same time as Anglesea.

In a signed statement, a copy of which Rebecca has obtained, he said that between 1975 and 1980 he was a detective sergeant at Wrexham and regularly visited Bryn Estyn in the course of his duties.

He says he saw Anglesea on at least two occasions, once in a corridor when Kelman was interviewing one of the boys.

This was during a period for most of which Anglesea claimed he’d never been anywhere near Bryn Estyn.

Kelman remembered the first incident well:

“A member of staff opened the door into the room where I was and I saw Gordon with him in the corridor.”

“It did not strike me as unusual. I got the feeling that the man was looking for somewhere to talk to him.”

“I didn’t speak to Gordon. He was in uniform.”

“The other time I saw him was in the car park outside the home.”

“He was either getting in or out of a car. It was as I was leaving.”

“At this time Gordon was a town Inspector.”

Kelman also says that Anglesea must have known Howarth:

“Any police officer who had contact with Bryn Estyn would know him.”

“Howarth always seemed to be around.”

“Any police officer going there would be there for a reason. You couldn’t just walk into the home.”

“A senior member of staff would want to know the reason for your being there.”

“More often than not, that senior member of staff would be Peter Howarth.”

But Kelman did not give evidence.

Rebecca spoke to him and he said he “was suffering from severe mental depression at the time.”

So his statement was never subjected to cross-examination at the libel trial.

Kelman was not invited to appear as a witness at the North Wales Child Abuse Tribunal and so his evidence was not tested there either.

♦♦♦

THE DEFENDANTS also tried to undermine Anglesea’s credibility about the reason for his sudden decision to resign early in 1991.

In his Proof of Evidence he stated that he retired in April 1991 even though he could have gone on his full pension much earlier.

“I eventually retired after 34.5 years.”

“I had been diagnosed as a diabetic and had lost the sight in one eye. I therefore decided to take my pension.”

During cross-examination George Carman QC asked him if he had been interviewed by the then Chief Constable David Owen on 13 March 1991.

“No, sir,” replied Anglesea.

Carman asked if he’d gone to the chief’s office that day and Anglesea again said “No, sir.”

“Well,” said Carman, “I am suggesting to you that on the 13th March 1991 you were interviewed by the chief constable about your travelling expenses.”

“No, sir,” replied Anglesea.

Carman then asked if he had been interviewed by anyone else.

“Well, yes, by the assistant chief constable.”

It then emerged that he was told he would have to be suspended while an investigation took place into his expenses.

GEORGE CARMAN, QC

George Carman, who represented the London media in the case, was the most famous libel barrister of his day. He cross-examined Gordon Anglesea.

Photo: © Photoshop

George Carman, who represented the London media in the case, was the most famous libel barrister of his day. He cross-examined Gordon Anglesea.

Photo: © Photoshop

In his final address to the jury Carman said:

“Well that took a long time to come out, didn’t it?”

“That’s hiding it, trying to avoid it, that shows he’s not quite the frank man he would have you believe.”

In his summing up, Sir Maurice Drake told the jury about the difference between libel actions and criminal cases.

In criminal cases, a jury has to be satisfied beyond reasonable doubt before a guilty verdict can be reached.

In a libel action, the verdict is based on the balance of probabilities.

However, he added that the balance of the scales depended on the gravity of the alleged libel.

“The more serious the charge, the further down the scales have to go.”

“So in this case, where the charge against Gordon Anglesea is just about as serious as you could consider, the evidence required to prove the Defendants’ case must be that much stronger.”

After nine hours of deliberations, the jury found for Anglesea by 10 votes to 2.

Looking back on the case, Sir Maurice told Rebecca:

“In my view the evidence was very finely balanced.”

“My summing up was, I believe, absolutely free of any indication of what I felt the verdict should be.”

“I would not have been surprised if the jury had found for the defendants.”

“I believe that it was the evidence of Mrs Anglesea which tipped the scales in favour of the plaintiff.”

“Many jurors would find it difficult to believe that a married man could have a full sexual relationship with his wife at the same time as he was committing buggery …”

The jury never got to decide what the damages should be.

The two sides agreed that Anglesea should receive £375,000 in damages together with his costs.

The Independent on Sunday and HTV each agreed to pay £107,500 in damages.

Private Eye and The Observer each agreed to pay £80,000.

The final bill for the four defendants, including legal bills, would have been somewhere between £3-4m.